I’ve always been a believer in the quip that “America has three cities: New York, San Francisco and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.” It gets at the uniqueness of some terrains and urban centers and the infinite monotony of others. Having grown up in the Midwest and later moved to the coasts, I find the quip stands up extremely well.

A few weeks ago, I traveled to Miami for the first time. It’s a dichotomy of a city — a place unique in culture and people and history and its attachment to Latin America, but with an architectural style and urban plan that is just brutally, concretely, boring. And frankly impossible to use — every single trips around the city ended up requiring an Uber, and every single time that Uber was surging 2.0x or above. A single two mile trip downtown that took about 9 minutes cost $26 with fees, tax, and tip. This is a fanciful place.

The weather was absolutely pristine and enviable though, and I can see the allure. April sells Miami unlike any place I have ever been — the music, the breeze, the beaches, the polyphonies — just the vibe. I get it.

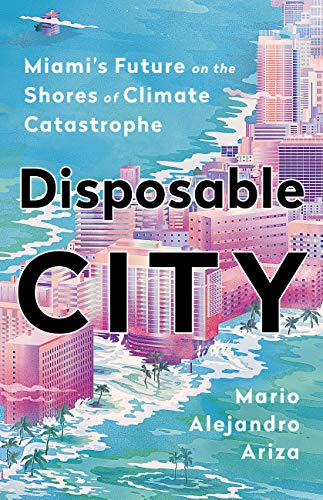

Connected to the trip, I delayed read Mario Alejandro Ariza’s recent book “Disposable City: Miami's Future on the Shores of Climate Catastrophe.” Given a lot of the work I have been doing around disaster response, it seemed the perfect antidote to the positivity that emanates from the Magic City.

It’s a negative if not dreary book, and positively among the global warming library, it tries to expand the panorama of people who are acting and reacting to the rising tides that threaten to subsume Miami back into the swamp. Given Ariza’s cultural background from the Dominican Republic, we can connect and feel the voices of people that have truly built Miami into what it is, and are so often overlooked in the more scientific and academic works that plague the field.

The book is at times angry and sorrowful. Angry that so few seem to care about what is coming. Writing in the early pages, Ariza astutely observes that “Many politicians here prefer to speak exclusively about ‘sea level rise,’ as if the ocean were rising of its own accord.” Sorrowful, because it is clear from almost any angle analyzed — environmental, financial, political, social — that Miami is doomed.

This is a melting pot of a book, where historical reviews are mixed with personal memoir along with field reporting from the wilderness and from the bureaucracies of city councils and courts that manage this strange metropolises. It’s also promiscuous in its reporting, interviewing academics and civic leaders and politicians and random bystanders on the edge of the precipice.

Unfortunately, it’s occasionally interesting, but just occasionally. This book has a point of view and the invective to match, a stance that is understandable given the circumstances but histrionic with its repetition. And speaking of repetition — I have never seen a writer so gratingly describe the physical features of every single interview subject they meet. “A stout older man with a broad face, soft voice, and a crooked finger on his right hand” — we get such depictions dozens of times throughout the book. One wonders what the crooked finger is doing for the reader?

I walked away from the book in much the way I (didn’t get to) walk away from Miami — it’s an interesting crossroads and intersection and case study of a time, a people, and a place. But I found myself empty in the end, and a few days later, didn’t really remember much about it at all.