It’s another year, and another year of great books. One of the goals of this year was to write more reviews of books that I have read — as you can see from the archives, that failed miserably except for a capsule blog post about Cixin Liu’s Three Body Problem. I am making no promises about this next year.

That said, there were a number of great books that I read this year, and I hope more people read them as well. As I wrote about last week, I am attempting to be more deliberate with what I am reading. So there is more fiction this year, and I hope that trend continues next year.

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

This was the single best book I read this year. First and foremost, it is an amazing novel about the challenges of a family on the edge of society trying to make it between two cultures, Korea and Japan. But at its heart, it is a meditation on the challenges each of us face as we are confronted with events far beyond our control.

Pachinko is a Japanese parlor game that’s sort of a more gambling-oriented pinball (Google for more careful discussion of the importance of the game to Japanese culture). While the operator has some control over the balls in the game, ultimately, those balls are going to bounce against obstacles, mostly on their own, and winning or losing the game has more to do with the odds of the parlor than any specific actions on the part of the player. Yet, the feeling of skill — of control — is critical to the belief that we have agency in a harsh world.

Lee managed to layer that high-level metaphor into the family at the heart of her novel. This is her second novel, and her craft is simply mesmerizing. At some point, I just got lost in the characters and the events they survive. As one can imagine, it’s a bittersweet novel, but one that I think provides a cautiously optimistic view on humanity.

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen

This book has a very different tenor than Pachinko. In this case, the book explores the challenges of the Vietnamese after many become refugees and are dislocated to the United States and elsewhere. While they are in some ways adopted into their new country, they also retain all of the hopes, animosity, and bitterness forged in the fires of that brutal war.

The author uses the occasion to deeply and critically analyze the missing voices of the Vietnamese people in the discussion of the Vietnam War. There is a major plot point around the making of what is presumed to be Apocalypse Now in which the character learns that ultimately the Vietnamese are never going to be given their due in the narrative. That trend has hardly changed in the pursuing decades.

Rather than only targeting one side, though, Nguyen managed to criticize basically everyone in the system. Wars don’t just happen, but require so many constituent pieces to sort of fuse together to make them work. The author’s ability to deeply flesh out characters, its refreshing plot device of the main character confessing the entire novel, and its use of metaphor and imagery are seared into my mind.

Seeing Like a State by James C. Scott

This is one of the great social science works of all time, and for good reason. Scott investigates the concept of legibility, which is how a state sees its subjects and domains. How does a nation tax? How does it know who a person is, what they own, or what they owe? Through case studies and analytical work, he shows how humans constantly are in war with states over classifications. The last name didn’t exist until the tax authorities needed better ways of individualizing people. This sort of deep insight alone is worth the book.

Scott goes one step further though and attacks what he calls “high modernism” — the movement among government and its bureaucrats with utopian dreams to remake society to fit models better. He condemns constructed capital cities like Brasilia, and World Bank agricultural operations all under this rubric. Governments always ignore the deep complexities of social interactions and ecosystems, because governments think in averages and statistics while real life is about systems. So farms that once had great resilience because of multiple corps are decimated after the World Bank demands a monoculture agricultural style, because their study shows that that should lead to better outcomes.

It’s a lengthy book, but eminently readable, and definitely worth reading as opposed to just glossing some summaries. It will make everyone think twice about what a government can really do, and it is also gets to the heart of what I call data politics.

Master of the Senate by Robert Caro

I have now read four of the five Caro works. Master of the Senate is considered probably his finest work, and I believe that. It’s an incredible look at how Lyndon Johnson goes from the most junior senator in the country to the majority leader in just four years — an almost impossible to fathom legacy that is still being felt today.

As with all great works, Master of the Senate is not easy to summarize. It’s best felt through its pages, as we see how each event that happened across the country was parlayed by Johnson to his advantage. I think the biggest lesson is that Johnson just constantly understood opportunity — not immediately, or innately, but he would look at the same situation a thousand times until he found a way out of a dilemma. And he always found a way.

Beyond the life lessons though, the book has to represent one of the greatest biographies ever written. The way you can feel each of the characters is absolutely marvelous. Unfortunately, I can’t recommend just diving into this part of the series (you can, and it works, but it is so much better to understand what came before). So get through the first two books in the series and learn what from the master.

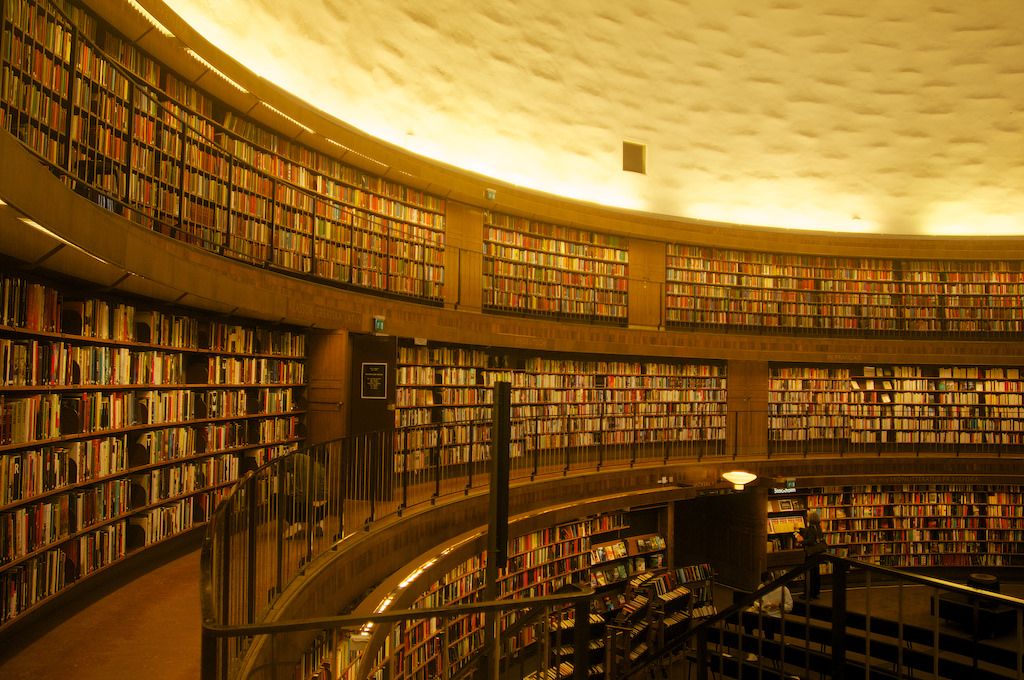

Photo by dilettantiquity used under Creative Commons.