The New Wave of Global Journalism (Key Platform 2014 Presentation)

The New Wave of Global Journalism

By Danny Crichton

I want to thank the organizers of Key Platform 2014 to speak today. My name is Danny Crichton, and I am a writer at TechCrunch, writing about startups in South Korea, Asia, and in Silicon Valley. Many people seem to think that much has changed over the last 50 years when it comes to journalism.

A History of

Little Change

That notion is false. Despite the incredible technological progression made in all kinds of industries like commerce, social communications, enterprise storage, security, and information retrieval, news content and journalism more generally hasn’t changed all that much over the past 50 years. I realize I am being a bit contrarian, but let me show you the evidence.

For instance, content today for news sites is developed much the way it has been for decades. Journalists around the world interview subjects, take photos and video, write up stories or maybe edit a short documentary, and then post it to the web. While technology has certainly made this process more streamlined through online editing tools, and the demands placed on journalists in producing content are higher today, the basics of the profession have really not changed all that much. Great content is visceral, engaging, interesting, and timely. That formula works as well during the 1960s as it does today.

The way we edit and curate our work has changed a little bit, but there has been far less interesting results here than many presume. Before the internet, the number of writers of content was manageably small, and a small group of people called editors acted as gatekeepers for content. If you could get an editor at the New York Times interested in your story – you were published. There was definitely a bias here, but the system was also quite simple to understand. Today, anyone can publish through blogs, on Twitter, or through Medium. Our editing and curation of articles has not yet caught up with this, so we rely on aggregation algorithms like Google News or Prismatic, personal streams like Pulse and RSS, or social networks like Twitter to recommend to us the best content. Because of the noise on the internet, content has become optimized for these distribution channels – leading to bold and simple headlines, articles made up of lists, and more emotional stories to get readers.

Perhaps the biggest disappointment is how little the presentation of news has changed over the years. It is hard to believe, but we are still using the same types of fonts and formatting that we used decades ago on the modern web today. This is a great example of how technologies have converged – it doesn’t matter whether you read the paper edition, online edition, or mobile edition of the New York Times, you are getting a single, seamless experience. To be fair, sites across the web have developed some interactive elements – videos, graphics, polls, etc. But even web-native news portals have followed the same news conventions as legacy media companies.

Finally, business models have remained pretty much the same on the internet. Advertising and subscriptions remain the bedrock of the media industry, representing most of the revenues of the industry. The only recent model change has been the incorporation of events and conferences as a revenue stream, an approach taken by parent company TechCrunch with its Disrupt conference, and this Key Platform conference by MoneyToday.

What has Changed?

Audience

Frankly, the supply side of news has not been that interesting. We have greatly increased the number of news writers, but the craft itself has not dramatically changed, nor has the way we present that to readers. However, what has changed is our readership, which has become distinctly global. Publications like the Guardian and the New York Times now have wide global audiences, and their stories are at the center of the online conversation. Readers consume news in more places, and at more times, encouraging more regularly updated news that is smaller in scope to be consumed quickly. Even though our readership has changed, we have not made much change to the way they experience and fund news.

But, new technology

is coming

Although the shift to mobile and the general convergence technologies of the last few years have not dramatically changed the news industry, there are several technologies I want to highlight that have the potential to fundamentally change the way news is consumed and funded. These technologies represent a new global wave coming through journalism, in which people around the world finally have access to global news reporters, and the ability to pay for that news outside of traditional channels like advertising and subscriptions.

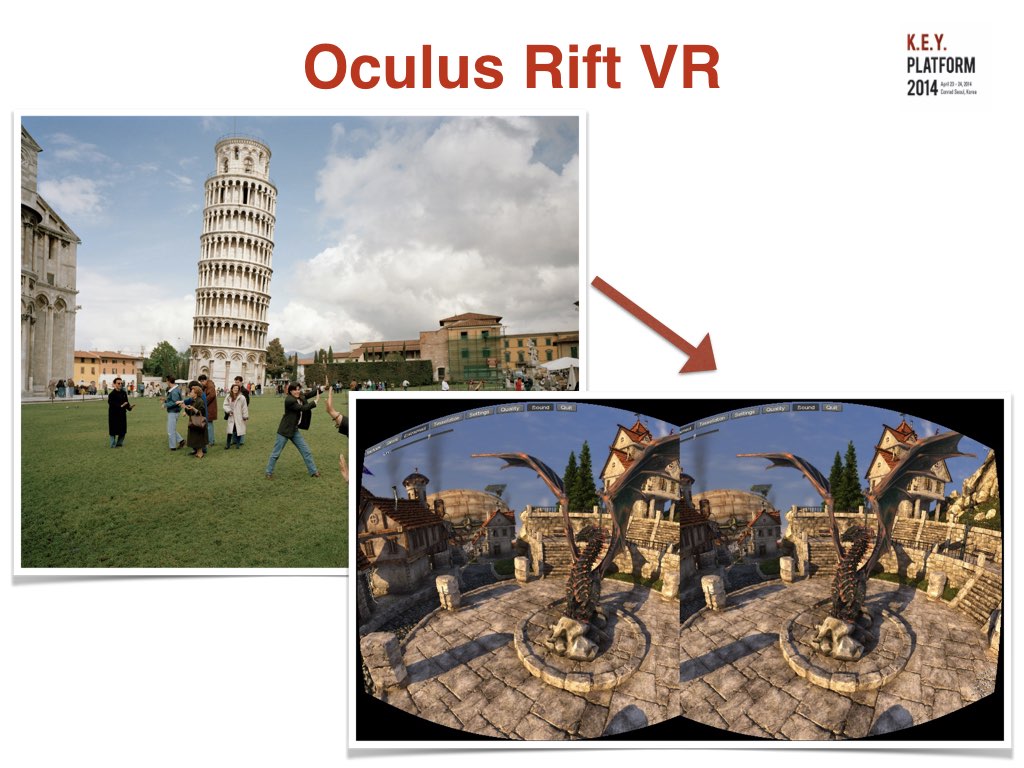

First, I want to talk about Oculus VR, the virtual reality company that was recently bought by Facebook for $2 billion. The company is developing a virtual reality headset that allows you to immerse yourself into another world. The device is essentially an LCD screen in front of your head attached to a sophisticated array of sensors that allows you to move your head, and have the image on the screen track those movements. Imagine playing a video game, but instead of holding a controller to move around, you can now just move your head naturally. It’s that simple. I personally have had the opportunity to use the device, and was frankly blown away at the quality of the experience, and the potential for virtual reality to remake entertainment.

But entertainment is just one facet of the potential of this type of convergence technology. I believe that news and journalism itself will be the biggest beneficiaries of this technology. For the first time, journalists do not have to report the news through a secondary medium like print or video. Instead, we can now witness news first-hand in a completely immersive environment. This is, in my opinion, the first truly new medium for news since television and video. We don’t just have to describe what is going on in a scene, but instead can transport the viewer into the world that we are describing. Imagine what war reporting would be like if we could literally experience it ourselves, or what a disaster like last week’s ferry sinking in South Korea would feel like in such an environment. Most importantly, this sort of medium is exclusive – you can’t multitask in a virtual reality environment like you can with a phone. Suddenly, our readers can attune their attention to the news and get more out of it.

It is not just readers that are going to be benefiting from this sort of technology. Tools like Google Glass can suddenly allow journalists to tell their stories simply by walking around. Suddenly, they don’t have to hold a video camcorder or photo camera in order to capture the scenes they are witnessing, but can instead be far more natural in engaging with their world. By creating videos with these technologies, we can feel as if we are actually talking to the interview subjects of the journalist, and seeing it from their perspective. In short, we are cutting down the boundaries of our existing media platforms, and creating more seamless experiences through convergence technologies.

Bitcoin is well-discussed, but one area where it has been less debated is its possible impact for journalism. For those not familiar, Bitcoin is a crypto currency – a type of money that is digital native and uses specialized cryptography to allow anyone to send money to anyone else in the world guaranteed without any knowledge of who they are. Today, our existing payments infrastructure is based around credit cards, which have exorbitant fees. Bitcoin has essentially no fees. There are two key features that Bitcoin offers for journalism – global payment, and micro payments.

Bitcoin allows anyone to transfer money across the world without fees. There is also no foreign exchange, because Bitcoin itself is a currency that is common for everyone. This has enormous implications for what can be done for media business models, because suddenly, readers around the world could potentially turn into paying customers. Currently, media sites often avoid subscriptions, because their user base can be so scattered across the world, it is difficult to handle the payments to make subscriptions successful. For the first time, media business teams have an option to collect subscription fees from anyone in the world – opening more channels for revenue than ever before.

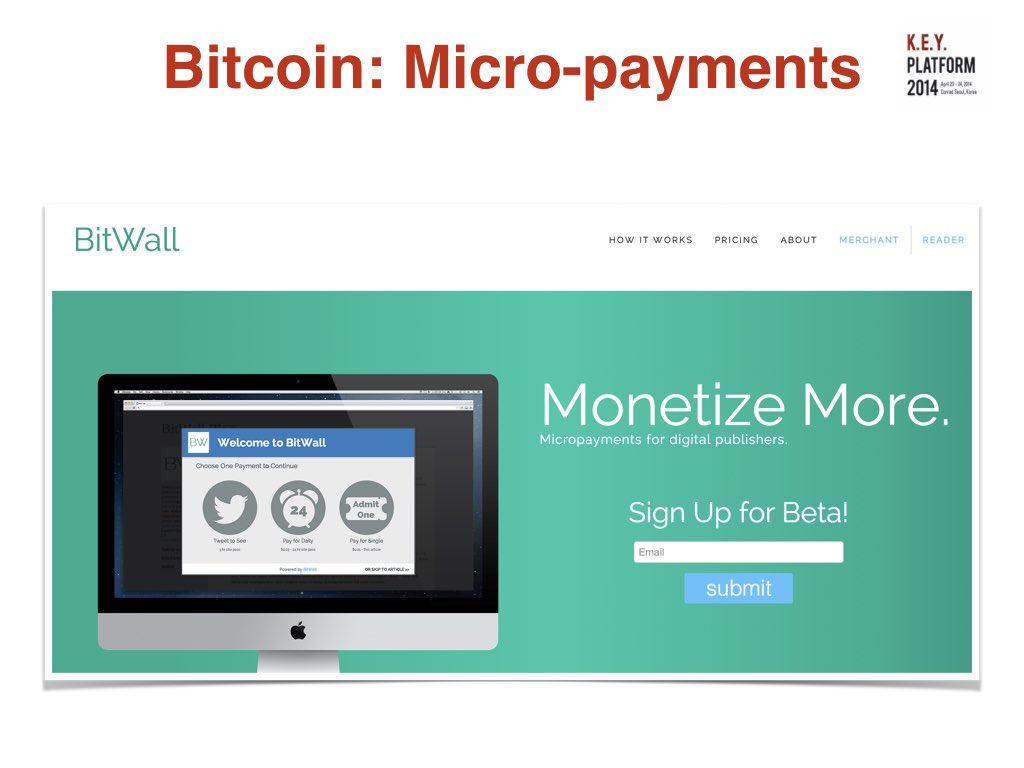

Bitcoins also have a unique property – they can be subdivided into arbitrarily small parts. That means that you don’t just have to pay $5 for an online content pass, a price high enough to cover the credit card fees and gateway fees. Instead, you can charge a micro-payment that might be as little 1 penny, or maybe even a fraction of a penny for a view of a video. This means that a media company can charge by the article, effortlessly, opening up a type of pay-as-you-go business model that has so far been impossible to build on the internet. Companies like BitWall are already starting to implement the technology needed to work here, but expect more to come in the coming years as we find novel uses for micro payments for media sites.

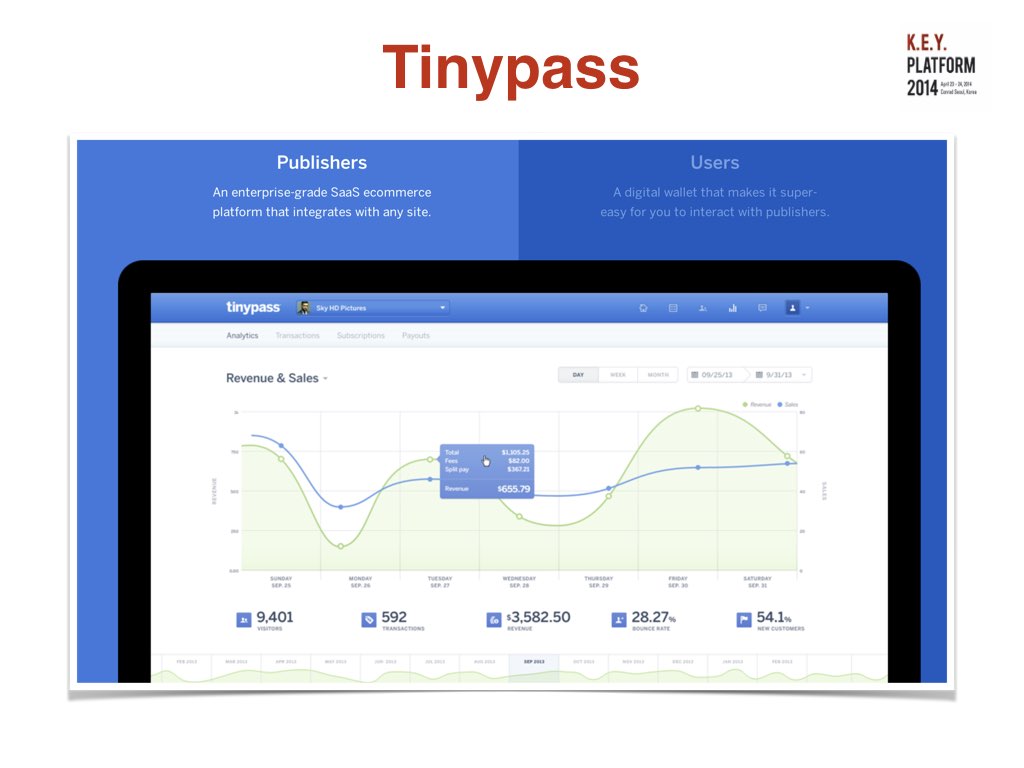

Even without Bitcoin though, we are starting to see better tools for creating scalable paywalls with the flexibility needed by the diversity of today’s media companies. This company, TinyPass is based in New York and they offer a full-suite of tools for enforcing a variety of paywall types, from per article to full monthly subscriptions. As a consumer, your information can be saved with Tinypass, so that you don’t have to repeatedly type in your payment information on every new website, but instead can carry it around you. Startups like Tinypass are changing the paradigm on how to think about revenues in the content industry. Today, there is far more sophistication and choice available to publishers, which can mean a greater diversity of business models depending on the goals of the producer.

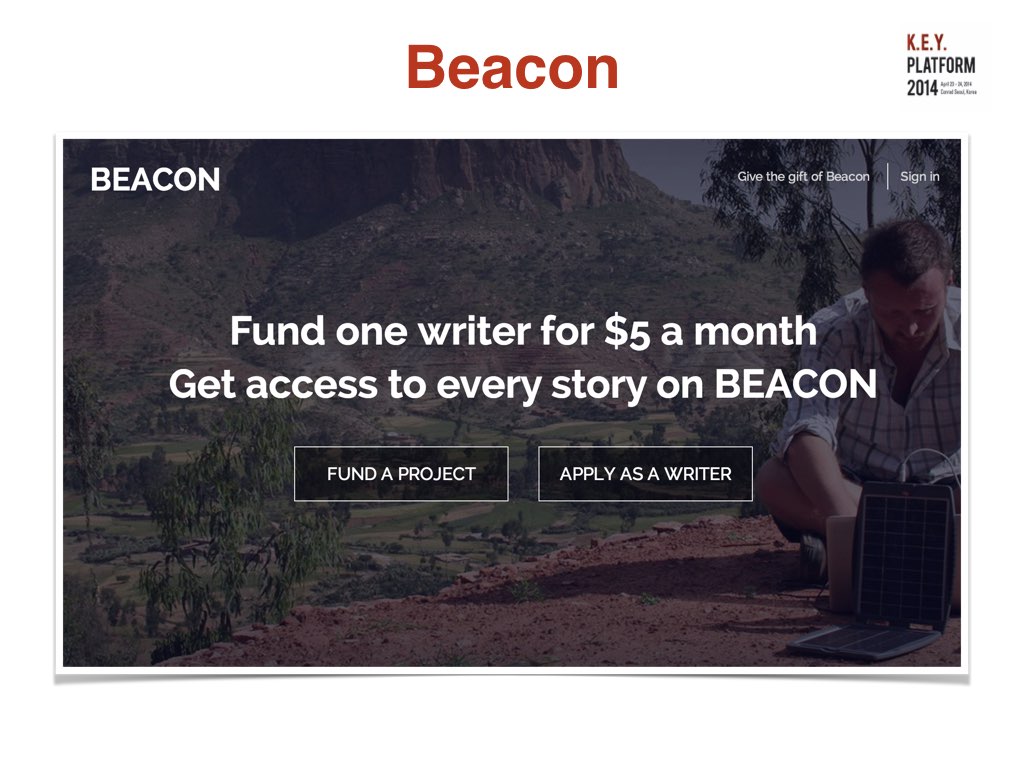

While monetizing content is certainly laudable, one large problem for content producers like writers is that they can lack the income needed to develop their stories. Beacon, a startup based in San Francisco, is hoping to change that. Through a crowdfunding model, Beacon connects funders concerned about a variety of issues like climate change and health care with writers who are experts in those fields. The idea is to provide a whole new means for writers to find a source of income while also building great content for the world. One of the issues with toddy’s media landscape is that content development is often closely associated with personal branding, leading to a huge focus on areas like marketing and business strategy. With startups like Beacon, we may expand the range of content that the internet is able to fund.

A Truly

Global Journalism

For the first time, we have the ability to imagine how a truly global journalism can function. Through technologies like Oculus Rift, journalists can move our readers directly to the site, no matter when they may be. Bitcoin and Beacon allow us to fund this journalism globally as well, creating an evolving business model for a very different type of readership.

Soon, everything

will change

The media industry has survived through layoffs and structural reforms that have cut their costs. But the industry has barely done anything to change over the last two decades despite the complete change in the technology landscape. However, this history is going to change very quickly in the coming years. We are suddenly going to rebuild journalism from the ground up, with journalists funded by benefactors and readers in a highly-netwoked business model in which the focus is on the journalists themselves more than the media companies they work for. There are certainly concerns to pay attention to, such as the need to create independence for journalists to pursue stories that may not be popular or profitable, for instance. But if we are able to handle the conflicts of interest such a networked model of journalism will bring, we will have the opportunity to both increase the scope of journalism, while also increasing its quality. That’s a world I look forward to viewing in real life, or at least, through my virtual reality glasses.

The New Wave of Global Journalism

By Danny Cric